Olive Morris: The Life and Legacy of a British Black Power Pioneer

The history of social justice in Britain is filled with names we should all know, yet many remain in the shadows. Among the most significant is Olive Morris. A force of nature, a community organiser, and a radical visionary, Olive Morris dedicated her tragically short life to fighting the intertwined oppressions of racism, sexism, and classism in 1970s Britain. Her work, centred in the heart of South London, laid foundational stones for the Black British community’s self-determination, the squatters’ rights movement, and the development of inclusive, Black feminist politics. To understand the evolution of modern British activism, one must understand the indelible mark left by Olive Morris. This is the story of a woman who, in just 27 years, became an icon of resistance and a beacon of community power, whose legacy continues to resonate powerfully today.

Early Life and Formative Experiences

Olive Elaine Morris was born in Harewood, Jamaica, on June 26, 1952, and arrived in Britain as a child in the early 1960s, part of the Windrush generation. She grew up in South London, a vibrant and culturally rich area that was also a frontline for the racial tensions of the era. From a young age, she was acutely aware of the systemic racism that shaped the lives of Black people in Britain, from discriminatory housing policies and biased policing to overt racial violence on the streets. These early experiences of being an Afro-Caribbean woman in a predominantly white society were not just abstract concepts; they were daily realities that forged her political consciousness and ignited a fierce determination to challenge the status quo.

Her formal education within the British school system was, by many accounts, a frustrating experience, often failing to engage her brilliant and critical mind. It was outside the classroom, in the streets and communities of Brixton and Battersea, that her real education took place. She immersed herself in the burgeoning Black Power movement, finding intellectual fuel in the works of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and the Black Panthers, while also connecting with a network of young, radical Black activists. The political ferment of the late 1960s provided the perfect incubator for her talents, transforming personal grievance into a powerful, organised collective action that would define the rest of her life.

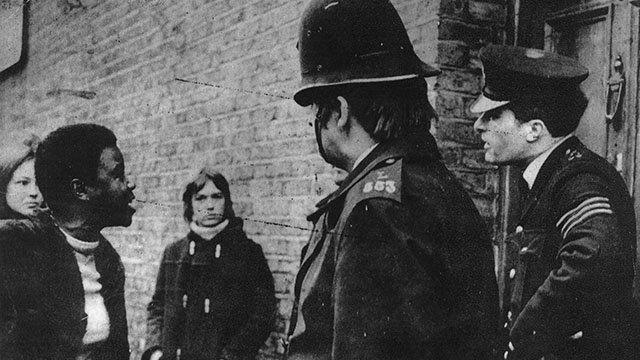

The Activist is Forged: The 1969 Desmond’s Hip City Incident

A single, brutal event in 1969 catapulted the 17-year-old Olive Morris into the forefront of the Black struggle in Britain. The incident occurred outside Desmond’s Hip City, a record shop in Brixton that was a cultural hub for the Black community. A Nigerian diplomat was being violently arrested by police, a common scene reflecting the aggressive over-policing of Black spaces. Witnessing this, Morris intervened to challenge the officers’ actions. In response, she was brutally assaulted, dragged into the police station, and subjected to a violent beating that included racial and sexual abuse, before being charged with assault and obstruction.

This traumatic encounter was a pivotal moment, solidifying her understanding of state power and its violent enforcement against Black bodies. It was not merely an arrest; it was a public demonstration of the racism embedded within the British justice system. The incident, however, did not break her spirit. Instead, it became a catalyst, a story that galvanised the community and cemented her reputation as someone fearless and unwavering in the face of oppression. It moved her from being a participant in the movement to a recognised leader, one who had personally endured the system’s brutality and emerged more determined than ever to dismantle it.

Her subsequent trial, where the charges against her were eventually dropped, became a rallying point. The Black community mobilised in her support, seeing in her their own struggles and resistances. This event demonstrated the power of collective defence and the importance of documenting police brutality. For Olive Morris, it underscored the inextricable link between community organising and direct confrontation with oppressive institutions, a strategy she would refine and apply for the rest of her career as a radical activist.

The Black Panther Movement in Britain

Olive Morris’s political home became the British Black Panther Movement (BBPM), an organisation inspired by, but organisationally distinct from, the American party. The BBPM adapted its ideology to the specific context of British racism, focusing on community survival programs and grassroots organising. Morris joined the Brixton branch, quickly rising through the ranks due to her intelligence, dedication, and formidable organising skills. The BBPM provided the structure and ideological framework through which she could channel her activism, focusing on practical support and political education for the Black community.

Within the Panthers, Morris was deeply involved in their core initiatives, which included running a Saturday school to supplement the Eurocentric education Black children were receiving. She also participated in the group’s newspaper distribution, legal aid programs, and campaigns against police harassment. This work was crucial because it addressed the immediate, material needs of the people while simultaneously building a political consciousness. The BBPM wasn’t just talking about revolution; it was creating the infrastructure for community self-sufficiency, a principle that would guide all of Morris’s future endeavours.

Squatting as a Political Act

In the early 1970s, London faced a severe housing crisis, disproportionately affecting poor, working-class, and immigrant communities. Abandoned properties dotted the cityscape, symbols of neglect and speculative greed. Olive Morris, alongside other activists, saw squatting not merely as a solution to homelessness but as a radical political act. It was a direct challenge to the state and private landlords, a reclaiming of space and autonomy. She became a central figure in the squatters’ rights movement, helping to organise the takeover and rehabilitation of vacant buildings in Brixton, turning them into homes and community centres.

Her most famous squat was at 121 Railton Road in Brixton, a building that would become a legendary hub of radical activity for nearly two decades. Securing this space was a tactical masterpiece of collective action. Morris and her comrades physically occupied the building, fortified it against eviction, and navigated the complex legal battles to secure its future. This was not passive resistance; it was an assertive, confrontational strategy that demonstrated the power of people when they organise. The success of 121 Railton Road provided a tangible model for community-led housing and became a beacon for anarchists, anti-racists, and feminists across the UK.

Founding the Brixton Black Women’s Group

By the mid-1970s, Olive Morris, along with other Black feminists, recognised a critical gap in the political landscape. The white-dominated feminist movement often ignored issues of race and class, while the male-led Black power movements could be dismissive of sexism and patriarchal structures. In response, they founded the Brixton Black Women’s Group (BBWG) in 1973, one of the first autonomous Black women’s organisations in the UK. The BBWG was a revolutionary space where women could organise around the specific, intersecting nature of their oppressions.

The group’s work was multifaceted and profoundly practical. They ran advice sessions for women dealing with immigration issues, domestic violence, and housing problems. They organised political education classes, published a newsletter, and campaigned on issues like the controversial “virginity tests” imposed on Black and Asian immigrant women at airports. The BBWG created a sisterhood of support and resistance, ensuring that the struggles of Black women were neither marginalised nor silenced. It was a testament to Morris’s evolving political analysis, which understood that true liberation required a fight on all fronts simultaneously.

Academic Pursuits and International Solidarity

In 1975, Olive Morris began a degree in Economics and Social Science at Manchester University, a move that reflected her desire to deepen her theoretical understanding of the systems she was fighting. University was not an escape from activism but an extension of it. In Manchester, she immediately immersed herself in the local political scene, joining the Black Women’s Mutual Aid Group and the Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative. She continued to connect local struggles to global patterns of imperialism and capitalism, bringing a sharp, academic rigour to her grassroots organising.

Her time in Manchester also solidified her internationalist perspective. She was a staunch opponent of the apartheid regime in South Africa and a vocal supporter of liberation movements across Africa and the Caribbean. This global outlook was integral to her politics; she saw the fight against racism in Brixton as intrinsically linked to the anti-colonial struggles in Angola or Mozambique. For Morris, the university campus was another front line, a place to recruit, educate, and build solidarity across different struggles, always linking theory with direct, practical action.

The Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent

Upon returning to London after her studies, Olive Morris co-founded one of her most ambitious and impactful projects: the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD). Formed in 1978, OWAAD was a national umbrella group that aimed to unite women from across the diaspora, recognising that their shared experiences of racism and sexism created a common ground for political action. It was a bold attempt to build a broader, more powerful coalition than had existed before, moving beyond localised groups to a national force.

Laura Alvarez: A Comprehensive Exploration of Her Multifaceted Career and Impact

OWAAD’s national conferences attracted hundreds of women, providing an unprecedented platform for discussion, strategy, and solidarity. The organisation tackled a wide range of issues, from immigration law and education to health and reproductive rights. It played a crucial role in the famous “Grassroots” black women’s newspaper and was instrumental in mobilising support for the New Cross Massacre campaign. OWAAD represented the zenith of Olive Morris’s organising prowess, demonstrating her ability to think and act on a large scale while remaining firmly rooted in the needs and voices of the women she served.

A Comparative Look at Olive Morris’s Key Organisations

The following table breaks down the primary organisations Olive Morris was involved with, highlighting their distinct focuses and her specific roles within them. This illustrates the strategic breadth of her activism.

| Organisation | Primary Focus & Context | Olive Morris’s Key Role & Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| British Black Panther Movement (BBPM) | Community Survival & Anti-Racism. Responded to systemic racism, police brutality, and educational neglect in the late 1960s/early 70s. | Organiser & Educator. Participated in running Saturday schools, legal aid, and community patrols. Helped distribute the movement’s newspaper and build grassroots support in Brixton. |

| Squatters’ Movement (121 Railton Road) | Housing Rights & Reclaiming Space. Addressed the housing crisis and property speculation by directly occupying vacant buildings in the 1970s. | Pioneering Tactician & Lead Organiser. A central figure in the physical occupation and legal defence of 121 Railton Road, establishing a long-lasting social centre and model for direct action. |

| Brixton Black Women’s Group (BBWG) | Black Feminist Autonomy. Created a specific space to address the intersection of racism and sexism, which was overlooked by other movements (1973). | Co-Founder & Core Organiser. Helped establish one of the UK’s first autonomous Black women’s groups, focusing on practical support, political education, and campaigning on issues like immigration abuse. |

| Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD) | National Coalition Building. Sought to create a united national front for Black and Asian women to increase political power and visibility (1978). | Co-Founder & National Strategist. Played a key role in founding this umbrella organisation, helping to organise its influential national conferences and connect local groups across the country. |

Untimely Death and Immediate Aftermath

In 1978, Olive Morris was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Despite her fierce spirit, her health deteriorated rapidly, and she passed away on July 12, 1979, at the age of just 27. The news sent shockwaves through the communities she had helped to build and empower. Her death was not just the loss of a young life; it was a devastating blow to the very fabric of the movements she championed. The grief was profound, mixed with a sense of urgency about continuing the work to which she had dedicated everything.

The immediate aftermath of her passing was marked by an outpouring of tributes that reflected the vast scope of her influence. Friends, comrades, and community members from the squats, the women’s groups, and the Black power circles gathered to mourn and to celebrate her incredible legacy. Obituaries in radical publications painted a picture of a beloved, fearless, and indispensable leader. The question on everyone’s mind was how to honour such a monumental life cut so tragically short, a question that would eventually lead to concerted efforts to preserve her memory for future generations.

The Enduring Legacy of Olive Morris

The legacy of Olive Morris is a powerful and living one, reclaimed from the brink of historical obscurity through the determined work of later activists, scholars, and her own community. For years, her story was known primarily to those who had worked alongside her, a quiet legend in activist circles. However, since the early 2000s, there has been a concerted effort to ensure her contributions are recognised and celebrated publicly. This has taken many forms, from local history projects and academic theses to public art and official commemorations, ensuring that the name Olive Morris is spoken and remembered.

Perhaps the most visible symbol of this legacy is the Olive Morris Memorial Award and the ongoing campaign that successfully lobbied to have her image featured on a local Brixton currency, the Brixton Pound. Furthermore, her inclusion in the “100 Great Black Britons” list firmly re-established her in the national consciousness. These acts of remembrance are not merely symbolic; they are active interventions in the writing of British history, insisting that the contributions of Black women like Olive Morris are central, not peripheral, to the nation’s story. Her life continues to inspire new generations of activists fighting for racial, social, and gender justice.

As scholar and activist Stella Dadzie, a contemporary of Morris, once reflected:

“Olive was one of those people who made things happen. She had a clarity of vision that was quite extraordinary for someone so young. She wasn’t just talking about change; she was on the front lines, building the infrastructure for that change with her own hands. In the squats, in the meetings, on the streets, she was a force you couldn’t ignore.”

Why Olive Morris Was an Uncompromising Visionary

What set Olive Morris apart was her remarkable ability to connect different struggles without diluting the specificity of any of them. She never saw the fight against racism as separate from the fight for housing, nor the battle against sexism as distinct from the class war. This holistic, intersectional approach—though the term was not in common use then—was years ahead of its time. She understood that power was multifaceted and that liberation had to be similarly complex, weaving together multiple strands of resistance into a stronger, unified whole.

Her personal fearlessness was the engine of her strategic brilliance. She was unafraid to confront police officers, landlords, or bureaucratic institutions. This courage was not reckless; it was calculated and rooted in a deep belief in the righteousness of her cause. She empowered those around her to be equally brave, demonstrating that ordinary people, when organised, could challenge seemingly insurmountable structures of power. Olive Morris was a visionary because she didn’t just imagine a better world; she built tangible, functioning pieces of it in the shell of the old, from the squats that provided homes to the groups that provided political voice.

Conclusion

The story of Olive Morris is more than a historical account; it is a blueprint for radical, effective, and compassionate activism. In her brief 27 years, she demonstrated the profound impact one dedicated individual can have when their life is committed to the service of their community. From the streets of Brixton to the lecture halls of Manchester, from the squats of Railton Road to the national conferences of OWAAD, she fought tirelessly against the intersecting forces of oppression. The legacy of Olive Morris is not frozen in the past. It lives on in every community garden planted on a derelict lot, in every mutual aid group formed during a crisis, in every call for a more inclusive and truthful history, and in every young activist who discovers her story and finds the courage to continue the fight. Remembering Olive Morris is not simply an act of historical recovery; it is an active commitment to the principles of justice, self-determination, and collective power for which she so brilliantly lived.

Frequently Asked Questions About Olive Morris

Who was Olive Morris and why is she significant?

Olive Morris was a seminal Jamaican-born British activist and a key figure in the 1970s Black Power movement in the UK. Her significance lies in her fearless community organising around squatters’ rights, the founding of autonomous Black women’s groups, and her intersectional approach to fighting racism, sexism, and classism. The life and work of Olive Morris provide a critical framework for understanding Black British history and grassroots activism.

What was Olive Morris’s role in the squatters’ rights movement?

Olive Morris was a pioneering leader in the squatters’ rights movement, using the occupation of vacant buildings as a direct action against the housing crisis. She was instrumental in establishing the famous squatted community centre at 121 Railton Road in Brixton, which she helped secure and defend, turning it into a long-lasting hub for radical politics and community support.

How did Olive Morris contribute to Black feminism in Britain?

Olive Morris was a foundational contributor to Black feminism in Britain by co-founding the Brixton Black Women’s Group and the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD). These groups created essential spaces for Black and Asian women to organise autonomously, address issues specific to their experiences, and build a national coalition that challenged both racial and gender-based oppression.

What happened to Olive Morris?

Olive Morris died tragically young at the age of 27 in July 1979 after a short battle with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Her untimely death was a devastating loss to the numerous social and political movements she helped build. Her passing galvanised efforts to preserve her memory, leading to the posthumous awards and commemorations that help keep her legacy alive today.

How is Olive Morris remembered and honoured today?

The memory of Olive Morris is honoured through several initiatives, including the Olive Morris Memorial Award, which supports young Black women in activism. Her image was featured on the Brixton Pound note, and she was voted onto the “100 Great Black Britons” list. Ongoing projects by historians and activists continue to document and promote her story, ensuring her contributions to British social justice are not forgotten.